|

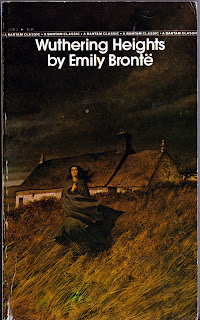

| The cover of the edition I first read |

[Like most of us, my

teens and early twenties were wasted years. I was studying (the word should be

interpreted in the broadest possible terms) at a college whose idea of culture

was ‘Bollywood Nite’ at the Annual Day. I was sitting in classrooms with people

whose preferred appellations for women were ‘chhavi’, ‘item’ and ‘chamiya’ and considered any girl who wore jeans to be

a slut.

However, at some point

in my post-graduation, we were given the opportunity to write a 'Book Review

that brought out the various power equations and conflicts that could happen

within human relations'. While I didn't really understand what that sentence

meant, I caught the first two words and went on and wrote a Review of

'Wuthering Heights', a book that, to me, has a near-holy status.

It was a story that grew

in the telling, and by the end of it, I had a review that was over six thousand

words long. It got me a good grade, but that was never the point. I was

writing a review of a Book that’s part of the standard syllabus across schools

wherever English is taught, and despite having no formal education in

‘Literature’ as it is taught in colleges, I gave it a shot. This is, in fact,

my first-ever ‘Book Review’.

Having nothing better to

do, I shall now proceed to put up this monster of a review on this Blog. The

longest single post ever, I think. The only editing from the original review as

written is in the last paragraph under the first section.

If you have spoiler

concerns, stop here.]

The Author, the Times and the Place

It is impossible to place Wuthering Heights as

a book into perspective without first knowing a little about its author, Emily

Brontë. She was the fifth of six children of an Irish Reverend, whose mother

died when she was three. Educated mostly at home by her father, Emily grew up

in the company of her two sisters, Charlotte and Anne, both of whom also went

on to become famous novelists, and her brother Branwell, a dissolute artist who

was, nevertheless, much doted on by his sisters. She spent most of her life in

the bleak moors of Yorkshire, which are the inspiration and backdrop of Wuthering

Heights. This isolation from the world outside proved surprisingly

conducive to the creative genius of the girls – the time spent with each other

and in solitude proving a fertile ground for the growth of their imaginations.

They wrote poetry and prose from a young age, and making up stories to fill in

the idle time rambling on the lonely moors must have been a necessity. Emily

and Anne had even created a whole fantasy world in their poems (commonly

referred to as the ‘Gondal’ Poems) – the world of Wuthering Heights is

often considered to be drawn from the Gondal world.

Wuthering Heights was

the only book its author ever wrote. She died at the age of 30, never living to

see the success and adulation her work would receive. Living most of her life

with her family or teaching at a school in Haworth, Emily lived what can only

be described as a very cloistered existence.

So perhaps it is remarkable that she

could have written as intense a book as Wuthering Heights. It is

remarkable that a woman in the prime of youth could have written a book of the

morbid splendour of Wuthering Heights. It is remarkable that a woman

could have created a character of such violent, wicked power as Heathcliff. But

then, Wuthering

Heights is a remarkable book.

|

| The woman who, to combat gender prejudice, had to write her book under the pseudonym 'Ellis Bell' |

If ever a tragically short life was fulfilled, Emily Brontë’s was. What she

left behind is immortal; it is a part of the collective conscious of the

English-speaking world.

I was young when I first read it – about twelve or thirteen, I can’t quite

remember – and have read it several times since. Each reading has been a source

of endless pleasure to me as it has to generations before me. It is not just

about the tragic, almost spiritually intense love story of Catherine and

Heathcliff – as Bonamy Dobree puts it, “After a hundred years, the verdict

goes that Wuthering Heights is itself an experience, a part of our sense of

existence, it colours our view of what life is about.”

As legacies go, that of Wuthering Heights

should be, and is, immortal. It is still being made into television and movies,

160-odd years after publication. The characters have lost much in the marketing

that goes with such resilience. Heathcliff is portrayed as a brooding hero – a

Gothic Edward Cullen, and the character of Catherine Earnshaw has also been

whitewashed. Such portrayals, inspired partly no doubt by how Sir Lawrence

Olivier and Merle Oberon (who so perfectly looked the part on screen and yet

managed to do little justice to the story) portrayed them way back in 1939.

|

| The book that lies on my bookshelf today |

The Setting

Wuthering

Heights is set on the bleak moors of Yorkshire. The action

confines itself to a small geographical area – the eponymous House of the Earnshaw family, Wuthering Heights, and that of the Lintons, Thrushcross Grange.

There are occasional references to the nearby village of Gimmerton, but it

hardly impinges on the narrative. The landscape Brontë describes is of wild,

uncultivated hills and crags, of cold wintry plains, and the warm comfort of

Thrushcross Grange. The houses are isolated – four miles separate the Grange

from the Heights, and the village is even further away. It is in this close

isolation that she traces the fortunes of the two families – the Lintons and

the Earnshaws, and the effect the foundling Heathcliff has on them. The houses themselves are indicative of the

occupants – Wuthering Heights located at a high altitude amidst cold biting

winds and the Grange in the calm, gentle plains.

It is the wildness that lends the book that flavour that leaves its mark, I

think. The title itself is aptly chosen – ‘Wuthering’ literally refers to the

effect of atmospheric tumults, a word describing the setting as perfectly as it

does the story. Long after you close the book, you carry the image of the stony

moors, the moss on the ground, the forbidding exterior of the Heights, the

grim, brooding figure of the ‘hero’ and the light-footed, wild step of the

heroine walking along paths only known to themselves, in your mind.

The Characters

Mr Earnshaw: Landowner, master of Wuthering

Heights

Heathcliff: A foundling, raised by the elder

Mr. Earnshaw.

Catherine Earnshaw: Daughter of Mr. Earnshaw

Hindley Earnshaw: Catherine’s elder brother

Edgar Linton: Master of

Thrushcross Grange

Isabella Linton: His sister

Catherine Linton: daughter of Catherine

Earnshaw (to avoid confusion, I shall refer to her as ‘Cathy’, the name by which her father referred to her)

Linton Heathcliff: Son of Heathcliff

Hareton Earnshaw: Son of Hindley

Ellen ‘Nelly’ Dean: Housekeeper and trusted

servant of the Earnshaws and Lintons at various times.

Lockwood: Heathcliff’s tenant

…and other minor characters

The Book

Wuthering Heights begins in

a dramatic fashion.

Lockwood, the tenant at Thrushcross Grange, calls on his landlord Heathcliff at

his house, the titular Heights, where he observes the taciturn protagonist, the uncouth

Hareton and the beautiful but haughty child-widow, Cathy. Forced to stay

overnight by a violent snowstorm, Lockwood finds himself sleeping in a tiny garret

that obviously was once the refuge of a certain Catherine Earnshaw, whose name

is scrawled multiple times on the wooden desk. Falling into a fitful sleep, he

dreams that he hears a knock on the window, through which the ghost of a little

girl unknown to him tries to enter the house.

“Begone!”screams

Lockwood, “I’ll never let you in, not if you beg these twenty years!”

“It

is twenty years,” replies the apparition, “I’ve

been a waif these twenty years!”

Lockwood’s screams bring to the room none other than his landlord himself, who,

on hearing what just transpired, throws open the window in a fit of desperation

and implores the ghost to

“Come

in! Come in! Cathy, do come. Oh do – once more. Oh my heart’s darling, hear me

this time, Catherine, at last!”

The ghost of Catherine fails to respond.

This passage sets the tone for the narrative, in its way. On his return to

Thrushcross Grange, where he has taken up his abode, Lockwood asks his

housekeeper, Nelly Dean, if she knows anything about the strange happenings and

behaviour of the residents of Wuthering Heights. From here begins the story of

Catherine and Heathcliff, as told by Nelly –

She takes Lockwood back some forty years, and tells of her being brought up at

the Heights, the daughter of the then-housekeeper, where she was a favourite of

the elder Mr. Earnshaw and a close friend of his son, Hindley. One fateful

night, Mr Earnshaw returns from a trip to Liverpool, whence he brings back a

dark, unknown boy, presumably an orphan whom he names ‘Heathcliff’ and proposes

to raise as his own.

Through his quiet, uncomplaining nature, Heathcliff quickly establishes himself

as a favourite of the old man, much to the annoyance of Hindley. Catherine, on

the other hand, develops a close bond with the boy. As children, the brutish

nature of Hindley is already evident, as is the headstrong, capricious nature

of his sister. Heathcliff’s true nature, however, awaits revelation.

What is interesting here is the effect on Hindley, who realises that in his own

house, he is subordinate to a foundling in his father’s eyes. Heathcliff knows

he can get anything from the old man, and that gives him a power over Hindley.

Hindley responds to this loss of power by resorting to physically beating

Heathcliff whenever opportunity affords. The latter never actually complains

about this to his benefactor, however, reserving his revenge for later.

The elder Earnshaw’s death is followed by the marriage of Hindley to Frances, a

pretty but empty-headed girl from the city. Now in charge of Wuthering Heights

and having power over Heathcliff, Hindley looks to exact revenge on Heathcliff

for perceived slights. Reducing the boy to a common labourer, subjecting him to

beatings and ensuring his utter degradation become Hindley’s tools for doing

so. Heathcliff falls into a life of rustic drudgery and all-round decay. His

association with his tormentor’s sister, however, continues as before.

Catherine and Heathcliff are still close confidantes, friends and lovers – two

against the world.

A significant event takes place while Catherine and Heathcliff are about

fifteen – on a ramble across the moors, the twosome stray into Thrushcross Grange,

where one of the Lintons’ dogs bites Catherine. On recognising Catherine as

their neighbour’s daughter, the old Lintons invite her to stay with them until

she recovers her health. This stay lasts a month, and Catherine makes her

acquaintance with Edgar and Isabella Linton. The Lintons are a sharp contrast

to the Earnshaws – they are exceedingly genteel, living in an atmosphere of

luxury and elegance. The Earnshaws, no less rich, live in much harsher

conditions, partly because of the location of the Heights at the high altitude

and partly because they are more rugged by nature. Even physically the families

are very different – where the Earnshaws and their household are dark-haired

and strong, possessed of strong constitutions (a characteristic that extends to

Heathcliff), the Lintons are blond-haired and delicate. The nobler, ‘superior’

Catherine quickly establishes herself in a position of dominance over the

Lintons. The boy adores her, she fascinates the girl and the old couple dotes

on her. It doesn’t take long for Catherine to realise that she has this ability

to dominate people through the force of her beauty and will.

The Catherine who returns to the Heights is quite different from the wild

gypsy-like creature who left it. Dressed in the finest clothes the Linton’s

could give her, she now looks like quite the little lady and acts the part when

she returns to her home – until she meets Heathcliff. Then the acquired

elegance is forgotten and she flies to his arms even as he returns from a long

tiring day at the fields, dirty and shoddy. Noble or rustic, for Catherine, he still

remains in ascendance.

But the visit to the Linton’s is not forgotten. Hindley, recognising the

advantages that association with the Lintons would bring, takes steps to

further restrict the contact between his sister and his enemy Heathcliff, even

as he encourages visits from the Linton family. Yet, the ties between Catherine

and Heathcliff continue as strong as ever.

Several years pass. Catherine is now grown to a true beauty of a woman;

Heathcliff to a near-savage farm labourer. Edgar Linton is now a close friend

of Catherine’s and she finds herself torn between the handsome, gentle Edgar,

the life of easy comfort that he epitomises - and the dark, rough, impoverished

Heathcliff. The contrast between them, as Brontë describes it, as the contrast

between a “beautiful,

fertile valley” and a “bleak, hilly, coal country”. The death of

Frances Earnshaw in childbirth leaves Hindley devastated. He becomes an

alcoholic, violent in temper and dissolute in behaviour, even as Hareton, his son, grows up in constant

fear of his father. It is here that Hindley, in fact, loses control over his

son – Hareton hates his

father, who gives him only beatings and abuses, and becomes closer to

Heathcliff – this fact is significant as the story progresses. The power that

Hindley exercises over his son through physical coercion is also much inferior

to that which we later find Edgar Linton exercise over his daughter.

Matters come to a crisis when Edgar eventually proposes to, and is accepted by,

Catherine. The subsequent conversation between Catherine and Nelly, which is

overheard by Heathcliff, is the central passage of the book. Catherine, acutely

aware that the man she has just accepted is not the one she considers her soul-mate,

is racked with doubt as to whether she has done the right thing, and tries to

convince herself, much more than Nelly, in this regard.

|

| Nelly and Catherine (played by Merle Oberon in the 1939 movie) |

"I

love the ground under his feet,” says Catherine of

Edgar, “and the air over his head, and everything he touches, and

every word he says…so tell me Nelly, am I doing right?”

“Perfectly

right,” says Nelly, “And now, let us hear what you are

unhappy about. Your brother will be pleased, you will escape from a disorderly,

comfortless home, into a wealthy, respectable one; and you love Edgar, and

Edgar loves you. All seems smooth and easy: where is the obstacle?”

“Here,

and here!” responds Catherine, striking her forehead and

breast, “in

whichever place the soul lives. In my soul and my heart, I am convinced I am

wrong.”

The explanation follows swiftly as Catherine relates to Nelly a dream she had:

“…I

broke my heart with weeping to come back to earth; and the angels were so angry

they flung me out into the middle of the heath on top of Wuthering Heights

where I woke up sobbing for joy. That will do to explain my secret, as well as

the other. I’ve no more business to marry Edgar Linton than I do to be in

heaven; and if my brother had not brought Heathcliff so low, I shouldn’t have

thought of it. It would degrade me to marry Heathcliff now; so he shall never

know how I love him, and that, not because he’s handsome, Nelly, but because

he’s more myself than I am. Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are

the same; and Linton’s and mine are as different as a moonbeam from lightening,

or frost from fire…I cannot express it; but surely you and everybody have a

notion that there is or should be an existence of yours beyond you. What were

the use of my creation if I were entirely contained here? My great miseries in

this life had been Heathcliff’s miseries, and I watched and felt each from the

beginning: my great thought in living is himself. If all else perished, and HE

remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were

annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty stranger. My love for Linton

is a little like the foliage in the woods: time will change it, I’m well aware,

as winter changes the trees. My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks

beneath: a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I AM

Heathcliff. He’s always in my mind, not as a pleasure, any more than I am a

pleasure to myself, but as my own being.”

In these words does the headstrong Catherine express her love for the man whose

fate she has just sealed by promising to marry his rival, and brings out the

searing intensity of their feelings for each other. It is a love beyond love, a

feeling of belonging, of oneness that they share, an almost supernatural depth

that will eventually consume both.

Heathcliff, unable to bear the insult of Catherine’s words that it would

degrade her to marry him now, runs away from Wuthering Heights. A traumatised

Catherine suffers a stroke and brain fever from which she makes a slow

recovery. It is three years before she and Edgar get married, by which time the

elder Lintons have succumbed to the ravages of time. Nelly moves with her

mistress to Thrushcross Grange, hoping for a brighter, quieter future than the

past has been. And this, indeed, seems to be the prospect. Edgar is a devoted

husband, bending to his wife’s caprices, his sister dotes on her as well, “honeysuckles

embracing the thorn”, as Nelly puts it. There is no bending from

Catherine, who is as headstrong as ever, but her husband and his sister are so

careful of her tempers and of ruffling her feathers, as it were, that life at

the Grange settles into a form of domestic bliss. The domestic life of the

Lintons is entirely subservient to the whims of the woman of the house.

Catherine Linton is the queen in her domain, lording it over the gentle natures

of her husband and sister-in-law. And just as absolute power can sometimes be

generous, she lets them have their own way when the fancy takes her, and

considers herself very magnanimous indeed for doing so.

There is a difference here between the power exercised by Heathcliff over

Hindley while old Earnshaw was alive, that exercised by Hindley over Heathcliff

after his death and that now exercised by Catherine over her husband’s family.

The first was power emerging from influence – the influence that

Heathcliff had over Hindley’s father. The second

flowed from authority. Hindley was

the master of the house; he fed and clothed Heathcliff, and the option before

Heathcliff was to accept this authority or leave – with leaving Catherine not

an option, Heathcliff was effectively in Hindley’s control. Here, however, the control is voluntary – Edgar allows Catherine to have her own way for the love he bears for her and the fear he has of crossing her.

This state of affairs does not last for long. Heathcliff makes his long-awaited

(and feared) return, a quite different man from the one who had left – the

plough-boy is now a wealthy gentleman. The text is deliberately silent on where

and how he made his money and got his education – Emily Brontë presumably

wanting readers to make their own judgement based on their own temperament.

The first meeting of Heathcliff in his new avatar, Catherine and Edgar Linton

is described in great detail. On seeing her old playmate, Catherine reverts to

her old self – it is as though the years and the layers of reserve have peeled

away again. Nelly points out to Lockwood the marked difference between her new

master and her old acquaintance – the effeminate, peevish Linton and the manly,

solid Heathcliff. Catherine, dominant as always, persuades Edgar to accept

Heathcliff as a friend. Heathcliff confides to Nelly later that he had not

planned on staying long; being uncertain of the reception he would receive from

Catherine. The effusiveness, the excitement, the emotion of her reception to

him convinces him that the love she once felt for him is far from dead; his own

burns as strongly as ever. Finding Hindley has dissolutely gambled away most of

his inheritance, Heathcliff installs himself as a tenant of his old tormentor at

Wuthering Heights and cunningly plots his landlord’s downfall, taking advantage

of his gambling habit. A new side of Heathcliff is also revealed here – his avarice, as he moves towards taking

over the home where he was once brought as a waif.

Before long, Heathcliff is a more and more familiar visitor at the Grange, and

he and Catherine resume their former relations as nearly as they can. The long

walks on the moors are resumed, in spite of Edgar’s resentment. To Heathcliff,

this is a triumph over his hated rival. To Catherine, this is a vindication of

her earlier stand that he should never have left. She does not believe she

loves Edgar any less for loving Heathcliff more. But then her feelings for

Heathcliff are not love as we understand it – it is something well beyond that.

In his new position, Heathcliff is not Catherine’s greatest comfort, but rather

her greatest torment. His presence

reproaches her every moment with that she could have had. His constant

accusations to her of not loving him, of tormenting him drive her near the edge

mentally even as her pregnancy weakens her physically.

A complication arises when Isabella Linton falls in love with Heathcliff, much

to the despair of Edgar and Nelly. A misguided affection, a childish

infatuation with that which she cannot comprehend, Isabella, who commonly

accompanies her sister-in-law and Heathcliff on their rambles, believes herself

well and truly in love with her brother’s enemy. There is an essential

difference between her feelings for him and Catherine’s. Whereas Isabella is in love with an idea of Heathcliff, of

a ‘black knight’, as it were, Catherine has no such illusions. Where Isabella

builds up an idealized image of a person who does not exist, Catherine

plaintively and honestly says,

“Tell

her what Heathcliff is: an unreclaimed creature, without refinement, without

cultivation: an arid wilderness of furze and whinstone. It is a deplorable

ignorance of his character, child, and nothing else, which makes that dream

enter your head. Pray, don’t imagine that he conceals depths of benevolence and

affection beneath that stern exterior! He’s not a rough diamond, a

pearl-containing diamond of a rustic: he’s a fierce, pitiless, wolfish man.

He’d crush you like a sparrow’s egg, Isabella, if he found you a troublesome

charge. I know he couldn’t love a Linton; and yet he’d be quite capable of

marrying your fortune and your expectations.”

|

| Rosalind Halsted as Isabella Linton from the 2009 TV adaptation |

Tragically for her, Isabella Linton disregards this advice from the person who

knows Heathcliff best; they elope some weeks later.

But before that, takes place the big confrontation between Edgar and Heathcliff

that precipitates Catherine’s decline. Edgar, returning from a Church service,

finds his wife and his bété noire engaged in

a heated argument about Isabella. Already smarting under the accumulated

insults of his situation, the enraged husband tries foolishly to evict

Heathcliff from his home permanently. The physical confrontation that ensues

between the two leaves Edgar hurt, Heathcliff furious and Catherine a mental

wreck. She suffers another stroke, followed by delirium and brain-fever. Edgar,

crushed by his wife’s illness and sister’s desertion, becomes a recluse. He

cuts off ties with his sister entirely and even Heathcliff desists from

repeating his visits to the Grange.

It is worth observing here that Edgar is unable to assert his rightful

authority as the master of his own home in the face of Heathcliff’s

overwhelming physical superiority. Already he has ceded control in his

relationship with his wife to her; and to her, there is no tinge of

unfaithfulness in what she’s doing. It is worth recalling that there is no hint of a sexual relationship between Heathcliff and Catherine – the battle

is always on the plane of the mind

and heart. To Catherine, this is

insignificant – it is Heathcliff who rules her heart and mind; she can identify

with him, she feels what he feels, she hurts when he hurts, but her duties to

Edgar as a wife are distinct from this. To her, there is place in her life for

both Edgar and Heathcliff, but neither of the men in her life sees it that way.

Heathcliff resents the loss of physical possession of Catherine, Edgar cannot

bear his loss of Catherine’s spirit.

Letters from Isabella to Nelly reveal her quick disillusionment with her

husband. His brutish nature shines in full force on her, and the witty, laughing

girl is reduced to a depressive cynic who hopes that her husband’s hatred will

eventually lead him to kill her, delivering her from a fate she believes worse

than death. She describes domestic life at the Heights with Hindley, Hareton,

the fanatical servant Joseph and of course, her husband. Hindley and Heathcliff

are always at each other’s throat – the former constantly plotting ghastly

revenges on the latter – plots he is never sober enough to undertake. The only

thing standing between Heathcliff killing Hindley is Catherine – as long as she

lives, Heathcliff knows he cannot harm her brother. Meanwhile the child Hareton

is growing up without ever learning to read or write, doting on his father’s

tormentor. The house is now a dark, dingy hell-hole, frequented by Hindley’s

drunken companions by day and by the spectral Heathcliff at night.

Whatever love Isabella may have felt for her husband is crushed by him.

“He’s

not a human being,” says the unfortunate girl, “and he

has no claim in my charity. I gave him my heart, and he took and pinched it to

death; and flung it back at me. People feel with their hearts, and since he has

destroyed mine, I have not power to feel for him.”

Catherine’s recovery is slow but she does, eventually, come to. Her

condition is still delicate, and the doctor warns Edgar that they have only

delayed the inevitable. Under Edgar’s care she does, however, return to

consciousness, though her mind is still, as Nelly says, “seemingly

fixed on a point well beyond what she can see.”

Heathcliff, hearing of her recovery, insists on a meeting with

her – his ‘soul’s

torment’ as he calls her. Through threats of forced entry, he

coerces Nelly into facilitating a meeting – him Catherine recognises. The final

meeting of the two is portrayed in a moving, often wild conversation, as they

accuse each other of causing the other misery, all the while clasped in a tight

embrace.

“I

wish I could hold you,” says the dying woman, “till

we were both dead! I shouldn’t care what you suffered! What care I for your

sufferings? Why shouldn’t you suffer? I do! Will you forget me? Will you be

happy when I am in the earth?”

“Don’t torture me till I

am as mad as yourself!” is his only response.

Here it might be worthwhile to try and examine the relationship between Heathcliff

and Catherine. There is something unnatural about their feelings for each other

– it reaches the point of obsession in him, to her he is a need as fundamental

to her as breathing. Where and when who has the greater power in their

relationship is difficult to say. Certainly Catherine seems dominant – she gets

her own way most of the time. Without her restraining influence, Heathcliff’s

savage nature would have, no doubt, expressed itself in a much more violent way

on his enemies. He has a power over her too – the power to make her feel guilty

and miserable through constant reproaches and accusations, which eventually

lead her to her death, but Catherine’s power is more ‘absolute’ – she gets what

she wants by commanding it, the tragedy is that she rarely knows what she

really wants. He ends up exercising his power to destroy the one thing he loves

most. In their complex relationship, power equations shift like the shifting

tides; and the force of their love, like a force of nature, takes with it not just

their own destinies, but those of all who associate with them – Edgar,

Isabella, Hindley and their children.

The arrival of Edgar at this tryst results in their sudden parting – Catherine

faints, never to rise again, Heathcliff flees the scene. That night, the elder

Catherine dies in childbirth, leaving her husband devastated and her lover

desperate. She leaves behind the prematurely-born Cathy Linton, a forgotten

child, her birth as tragic as that of her cousin Hareton’s.

The same night, Isabella takes the opportunity to escape her torture, stopping

at the Grange on the way, telling Nelly of her intention to go to a place where

her husband can never find her, which she does, raising their son on her own,

without ever telling him who his father is or that he even has one.

Edgar’s reaction to his wife’s death contrasts sharply with that of Hindley

Earnshaw’s. Where the one plumbs the depths of despair, taking to drink,

neglecting his estate and his son, the other raises his daughter in memory of

her mother, as doting and loving a parent as child could ever wish for. Hindley

dies soon, possibly murdered by Heathcliff, mourned by none but Nelly Dean.

Edgar lives on, though he confesses that he would be much happier interred with

his beloved wife. Cathy grows up a pampered child, beautiful like her aunt, but

with her mother’s fascinating eyes, accustomed to having the world bend to her

will, though she is far more sweet-tempered than her mother. The tranquillity

of her existence is broken one evening when, out on a ride, she trespasses into

the land belonging to Heathcliff, who is now the owner of Wuthering Heights.

There she and Nelly encounter Hareton Earnshaw (Heathcliff is away on business)

who, to Nelly’s great anguish, has been made by Heathcliff what Hareton’s

father had made him – a handsome but uncouth, rustic boor, unaware of his own

lineage, rights or place in society. Ironically, Hareton, who has the most

right to feel wronged by Heathcliff, dotes on him. The meeting jars on Cathy’s

consciousness – the realisation that this boor is her cousin is treated by her

with disbelief; it is the first notice she has of the roughness that she will

have to endure.

The death of Isabella Heathcliff when Cathy is about thirteen results in Edgar

bringing her son Linton to the Grange, but Heathcliff claims him as his own

property, and Linton is sent to Wuthering Heights. There is little of

Heathcliff in Linton physically – Nelly describes him as a puny weakling,

lacking his father’s strength or his mother’s wit and spirit, though he has his

uncle’s elegance. But in his mean, vindictive nature is a pale reflection of

his father’s diabolical menace.

|

| Cathy reads Linton's letters |

A few years pass in peace until Cathy once again passes by the Heights. This

time she meets Linton and is instantly attracted to him. Heathcliff senses in

this an opportunity to avenge himself completely on his own enemy Edgar, and

encourages this romance. Nelly and Edgar’s efforts to thwart the budding affair

prove to no avail as the children fall into a violent infatuation. Edgar

Linton’s health begins to fail, much to Heathcliff’s pleasure. But so does

Linton Heathcliff’s – and this is a source of worry to his father. Not because

Heathcliff bears any love for his son – he scorns him – but because he cannot

bear that Linton should die before a marriage takes place between him and

Cathy. Finally he resorts to kidnapping the girl and forcing her into a

marriage even as her father lies on his deathbed. Her protestations that she

would marry Linton of her own accord, if only she could be allowed to see her

father one last time are ignored by the brute, as he and his son conspire to

keep her incarcerated at Wuthering Heights. Cathy loves her father – he is the

leading light of her life to the end, and perhaps that is the only comfort

Edgar Linton carries with him when he eventually dies in his daughter’s arms.

The only tinge of regret that Heathcliff has in this whole business is borne

out in his words to Nelly on seeing Hareton’s brutishness – a condition he

himself has consciously engendered, “One is gold put to the use of

paving-stones and the other is tin polished to ape a service of silver. MINE

has noting valuable about it; yet I shall have the merit of making it go as far

as such poor stuff can go. HIS (Hindley’s) had

first rate qualities, and they are lost: rendered worse than unavailing. And

the best of it is, Hareton is damnably fond of me!”

The end is swift and despairing for Edgar Linton, as he realises his rival’s

final triumph over him. His nephew follows him a few months later, leaving

Heathcliff sole master of the Heights and the Grange, his triumph over both his

enemies – Hindley Earnshaw and Edgar Linton complete – the property of both in

his hands, the son of the one reduced to a labourer in the house where he should

have been master, and the daughter of the other treated like a house-servant in

the house where she is, by rights, the mistress.

Nelly Dean’s narrative ends here. Lockwood makes a final visit to his landlord

before leaving, where Hareton Earnshaw and Cathy have a physical altercation

over her scorn of him and his mean treatment of her. Almost afraid to fall in

love with a woman with such a past, Lockwood determines to leave the county.

Lockwood’s return a year later brings to a close the story of Wuthering Heights. He

finds Heathcliff dead, Cathy mistress of the estate, Hareton her fiancé and

Nelly re-installed as the housekeeper at the heights.

Nelly’s description of Heathcliff’s final days is a revelation in itself. It is

as though he has finally seen the ghost of his long-dead love. He sees her

phantom everywhere. He starts going alone on rambles across the moors, across

the well-trodden paths that he and she had taken together in happier days. His

conversation too, seems directed at some unknown spirit – he shuns company ever

more than before. Hareton, a living image of his aunt, is unbearable for him to

look at, Cathy, thought but a little like her mother in appearance, is still a

shadow of her. “Those two are the only objects which retain a distinct

material appearance to me,” Heathcliff says of them, “and

that appearance causes me pain, amounting to agony. About HER I won’t speak;

and I don’t desire to think; but I earnestly wish she were invisible: her

presence invokes only maddening sensations. HE moves me differently: and yet if

I could do it without seeming insane, I’d never see him again! In the first

place, his startling likeness to Catherine connected him fearfully with her. O

God! It is a long fight. I wish it were over!”

It does get over soon enough - the end comes suddenly, with Nelly finding him

dead in the little garret where he and Catherine had played together as

children and where Lockwood had first seen her apparition. Even as a spirit,

Catherine’s power over Heathcliff is absolute – the apparition of his idée

fixée leads him on to his death. Perhaps she calls him to her.

Hareton and Nelly are the only mourners at the funeral. The courtship of

Hareton and Cathy, which begins some time before Heathcliff’s death, blooms

into a happy relationship.

It is interesting that even after they are betrothed, Cathy is never able to

turn Hareton against Heathcliff. No stories of his wickedness, of how he as

wronged both her and him can convince Hareton that his idol was false. This

relationship is perhaps the most incomprehensible – the deep love that Hareton

bears for the man who has deprived him of land and lordship and possibly killed

his father. The power Heathcliff exercises over the son of his old enemy is

that of a cunning manipulator over an innocent victim. Yet, for all

Heathcliff’s exultation, he bears a grudging affection for Hareton, seeing in

him a personification of himself when under Hindley’s power, an affection that

he never bears for his own son. Heathcliff’s power over his own son is almost

purely that of a physically stronger

man over a weaker. Filial ties are

non-existent between the two. Hareton, on the other hand, willingly subjects

himself to Heathcliff, and through his own obvious qualities gains a place in

the affections not just of Heathcliff but also Nelly and of course, eventually

Cathy. Linton never earns anyone’s affection – scorned by his father and

Hareton – but Cathy’s, and even that, Heathcliff avers, would not have survived

long if Linton had not died before he showed his wife his true nature.

|

| Cathy and Hareton |

As Lockwood leaves Wuthering Heights, Nelly tells him of how the country folks

insist that Heathcliff’s ghost still lingers – “Idle tales, you’ll say, and so say I.

Yet that old man by the kitchen fire affirms he has seen the two of them (when

he was) looking out of his chamber window, every day since his

death; and an odd thing happened to me about a month ago. I was going to the

Grange one evening, and I encountered a little boy with a sheep and two lambs

before him; he was crying terribly. ‘There’s Heathcliff,

and a woman, yonder, and I dare not pass them!’ he said!”

Lockwood makes his was back to Thrushcross Grange to spend one

last night before he moves on in his travels. As he passes by the Churchyard,

he stops to look over the graves of the three people whose history he is now so

well acquainted with. They lie side by side, together in death as they were in

life - Catherine’s in the middle, grey, covered by heath, Edgar’s only

harmonised by the turf, Heathcliff’s still bare.

“I

lingered around them, under that benign sky, listened to the soft wind

breathing through the grass, and wondered how anyone could ever imagine unquiet

slumbers for sleepers in that quiet earth.”

|

| Lawrence Olivier and Merle Oberon |

After reading all that, if you’re

still up to buying it, this is where you do it.